Memes – Archive 2

Please note: The images we’ve used in creating these memes are courtesy of talented Scottish, Irish, Welsh and American photographers who have been kind enough to either grant us permission or licence these as Creative Commons on Flickr. The Creative Commons licence they have been released under means you are welcome to share these images on your social media freely, provided you give credit to the original photographer and a link back to the CC licence, as we have done.

Memes | Archive 1 | Archive 2 | Archive 3

Original image by John McSporran

Original image by John McSporran

| Beannaich mi an latha, Anam agus corp, Beannaich mi an latha, Agus gach latha. |

Bless me this day, Soul and body, Bless me this day, And every day. |

Following on from the caimeachadh (“encompassing”) prayer we shared last week, this adaptation into a blessing could be incorporated into a daily routine as a morning prayer.

Prayers of potection and blessing can be thought of as being two sides of the same coin, in some ways at least: Blessings can be protective because they have a preventative element to them – they explicitly invite the good so that we might avoid the bad. Prayers of protection, on the other hand, explicitly prevent the bad to make way for the good. In this sense, starting our day with a blessing and finishing it with protection, then starting again the next day, can be thought of as a cycle – the coin ever-turning.

While some of us do formal prayers at an altar or shrine every morning, this prayer can also be said over your morning tea or coffee, as you take a moment to yourself before you start your day proper; as you get dressed or showered; as you begin your daily commute, or whatever suits your circumstances. You can address it to a specific deity, the ancestors, or whichever spirits you call on for these things.

Prayer from Children and Family in Gaelic Polytheism.

Original image by John McSporran

Original image by John McSporran

| Caimich mi a nochd, Anam agus corp, Caimich mi a nochd, Agus gach oidhche. |

Circle me this night. Soul and bodt, Circle me this night, And every night. |

Prayers for blessing and protection are a traditional part of our daily Gaelic Polytheist practice. This short prayer here is an example of a type of protective prayer called a “caimeachadh,” or “encompassing.” The encompassing may involve certain actions to help visualise being surrounded or encircled in the protection of the gods, spirits and ancestors (An Trì Naomh), such as turning around sunwise with the right hand outstretched in order to “draw” a protective boundary. This action may be referred to as the caim na corraig, “the encompassing of the forefinger,” or caim na còrach, “the encompassing of righteousness.”

In Ireland, similar methods of protection are found, using a stick of hazel instead of the forefinger to draw the circle (usually when you are outside and find yourself under threat from Otherworldly forces who might wish you harm). In Scotland, the eighteenth century travel writer Thomas Pennant describes the use of a branch of oak instead.

This simple caimeachadh (“encompassing”) prayer can be said at bedtime as part of a daily routine, by yourself or with a child (or children). The language should be simple enough for children to pick up, and it can also be useful for any adult who wants to keep things short and sweet.

This prayer doesn’t involve any overt actions that must be performed with it, though you can do this if you wish or if it feels necessary. You might like to visualise being encompassed by the mantle of Brigid as you address the prayer to her (“A Bhrìghde nam brot “ – “Oh Brigid of the mantle” – a traditional epithet for her), or, if you are saying the prayer with a child as part of their bedtime routine you could “draw” a circle around them using your right-hand forefinger. Alternatively, they may take comfort in being tucked up with a special blanket (or “mantle”) as you say the prayer with them. The child can be encouraged to leave the blanket out for Brigid’s blessing at Imbolc, as is traditional, so that the child might know and take comfort in it.

Certain ancestors could be addressed in addition to, or as an alternative to whichever deity or deities you might have a connection with, if that seems appropriate — a well-loved family member, such as a grandparent, who may have passed on but is still around in some way, perhaps. Just as you should trust your instincts on who to address in prayer, trust your child’s and follow their lead; it will be more effective and personal for them if you allow them to choose. If you aren’t sure who to address specifically then you can just keep it general and address the gods, spirits, and ancestors as a whole.

This prayer was originally adapted and published in Gaol Naofa’s Children and Family in Gaelic Polytheism, based on a prayer from Volume III of the Carmina Gadelica, pp340-341.

Collage with “White Horses” by HeHaden, and “Cow” by Marilyn Peddle

Collage with “White Horses” by HeHaden, and “Cow” by Marilyn Peddle

| Chaidh Brìde mach Madainn mhoch, Le càraid each; Bhris each a chas, Le ùinich och, Bha sid mu seach, Chuir i cnàmh ri cnàmh, Chuir i feòil ri feòil, Chuir i fèithe ri fèithe, Chuir i cuisle ri cuisle; Mar a leighis ise sin Gun leighis sinne seo. |

Brìde went out In the morning early, With a pair of horses; One broke his leg, With much ado, That was apart, She put bone to bone, She put flesh to flesh, She put sinew to sinew, She put vein to vein; As she healed that. May I heal this. |

The formula found in this Gaelic prayer, of repairing “bone to bone…flesh to flesh…” has an ancient pedigree and can be found in much older sources, such as in the Irish myth of Cath Maige Tuired, when Miach gave Nudau a new arm made of flesh, joining it “joint to joint of it, and sinew to sinew.” A ninth or tenth century Germanic manuscript uses the same formula and attributes it to Odin, while the far older Atharva Veda also echoes the concept. Modern versions of the prayer can also be found in English and Shetland dialects, too.

Aside from using this kind of prayer as an aid to physical healing, the formula lends itself more metaphorical uses as well, in prayers to help repair the bonds of a community, perhaps, as we discuss in our article Prayer in Gaelic Polytheism. With this in mind we’ve changed the final line from “Gun leighis mise seo — May I heal this” to “Gun leighis sinne seo — May we heal this.” At a time of such strife in the world as it is today, prayers for healing may also be an aid to peace and protection as well.

Original prayer from Alexander Carmichael’s Ortha nan Gaidheal Volume II, 1900, #130 (pp18-19). Some minor changes have been made to update spellings and add the proper accents; for commentary and notes on this see the above mentioned article (pp14-16).

Slàinte Mhath!

Collage with sunset image by Peter Broster

Collage with sunset image by Peter Broster

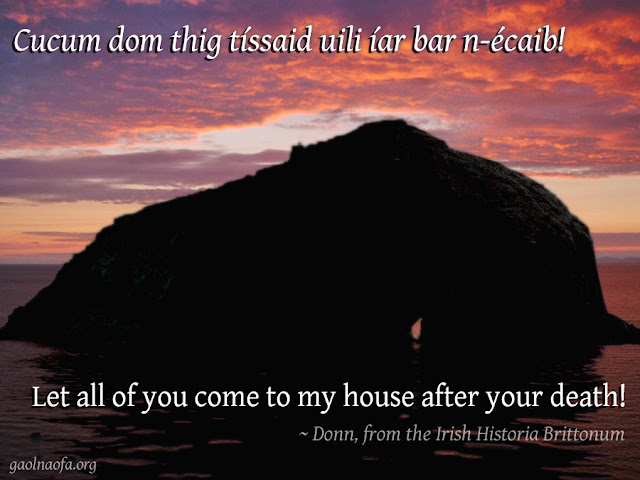

Cucum dom thig tíssad uili íar bar n-écaib!

Let all of you come to my house after your death!

Donn as a name is not uncommon in early Irish literature, but the most famous of these is Donn son of Míl, one of the kings of the invading Milesians who wrested control of Ireland from the Tuatha Dé Dannan.

In some versions of his tale, Donn refused to acknowledge the goddess of sovereignty, Ériu, and so was cursed to never again set foot on Ireland. During the Milesians’ attempt to land once again, the ship he was in was sunk and he was drowned.

His body was recovered and buried on an island, which was then named after him: Tech Duinn, The House of Donn. This island is most often associated the Bull Rock, off the coast of the Beara Peninsula, County Cork.

In other versions of Donn’s tale his death is more of an heroic sacrifice for his people, although he was still laid to rest on Tech Duinn. Because of this, as the first of the sons of Míl to die in Ireland, he declared, ‘To me, to my house, come ye all / After your deaths.’

Donn fulfills the role of “first ancestor” (or first male ancestor) and functions as lord of the dead. So strong was this connection that later Christian commentators would claim that all souls of the “heathen Irish” would travel to Donn’s House before going to hell; in an attempt to get the ancestors to turn from the old ways, some even tried to equate Donn with the Christian devil.

Text: With thanks to Sionnach Gorm.

Image by Jimmy Brown

The word Samhain comes from the Old Irish Samain, which is thought to mean ‘Summer’s End.’ It is primarily the name of the month of November, but is also used for the Gaelic festival that falls at the beginning of the month, and which also marks the beginning of winter.

In Ireland it’s Samhain, and pronounced “Sow-in.”* Festival celebrations begin on Oíche Shamhna – Samhain Night.

In Scotland it’s Samhain or Samhainn, pronounced ‘Sav-in’ or ‘Sow-een’. The festival begins on Oidhche Shamhna – Samhain Night.

In the Isle of Man it’s spelled Sauin, pronounced ‘Sow-in’. Celebrations begin on Oie Houney – Samhain Night.

* Pronunciation note: “Sow” to rhyme with “cow,” not “low.”

Original image: Colin Whittaker

Original image: Colin Whittaker

Original image: Chad K

Original image: Chad K

Original images: Michael Kötter (coo) and Wikimedia Commons (background)

Original images: Michael Kötter (coo) and Wikimedia Commons (background)

Original image: Knowth.com (used with permission)

Original image: Knowth.com (used with permission)

Original image: Moyan Brenn

Original image: Moyan Brenn

| Sith co nem. Nem co doman. Doman fo ním, |

Peace to the sky. Sky to the earth. Earth under sky, |

| Nert hi cach, án forlann, lan do mil, mid co saith. Sam hi ngam, gai for sciath, sciath for durnd. |

Strength in us all, a cup so full, full of honey, mead in plenty. Summer in winter, spear over shield, shield strong in hand. |

| Dunad lonngarg; longait-tromfoíd fod di uí, ross forbiur benna abu, airbe imetha. |

Fort of fierce spears; a battle-cry land for sheep, bountiful forests mountains forever, magic enclosure. |

| Mess for crannaib, craob do scis scis do áss, saith do mac mac for muin, muinel tairb tarb di arccoin, odhb do crann, crann do ten. |

Nuts on branches, branches heavy heavy with fruit, wealth for a son a gifted son, strong back of bull a bull for a poem, a knot on a tree, wood for the fire. |

| Tene a nn-ail. Ail a n-uír uích a mbuaib, boinn a mbru. Brú lafefaid ossglas iaer errach, foghamar forasit etha. |

Fire from the stone. Stone from the Earth wealth from cows, from the womb of Boann. From the mist comes the cry of the doe, a stream of deer after springtime, corn in autumn, upheld by peace. |

| Iall do tir, tir co trachd lafeabrae. Bidruad rossaib, síraib rithmár, ‘Nach scel laut?’ |

A warrior band for the land, prosperous land, reaching to the shore. From wooded headlands, waters rushing, “What news have you?” |

| Sith co nemh, bidsirnae. .s. |

Peace to the sky, life and land everlasting. Peace. |

In ancient Ireland, a great war is said to have taken place between the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Fomorians as they fought for the right to rule Ireland. The tale of this conflict is told in Cath Maige Tuired (The Second Battle of Mag Tured), and the final battle took place Samhain, with the Tuatha Dé Danann being victorious.

Conflict, death and chaos are common themes associated with Samhain in Irish myth and folklore, but out this conflict comes a resolution of peace. At the end of Cath Maige Tuired, the Morrígan (or Badb) relates a rosc (a particular type of Irish poem, which is often written in obscure or archaic language), proclaiming victory in battle, and giving a prophecy of things to come.

As Samhain approaches, it seems only appropriate to reflect on these themes, and the message of the Morrígan’s words. As a prayer for peace, you might also wish to incorporate the words into your celebrations. The images collated here (five in all) each contain a section of the prayer. You can also view our video of it, which we released on our youtube channel last year:

The original Irish is from Cath Maige Tuired. For more information about the translation, which is by Kathryn Price NicDhàna, see our article Prayer in Gaelic Polytheism.

| <– Back to Archive 1 | –> Forward to Archive 3 |